|

|

|

|

|

Sperm Competition in Flies

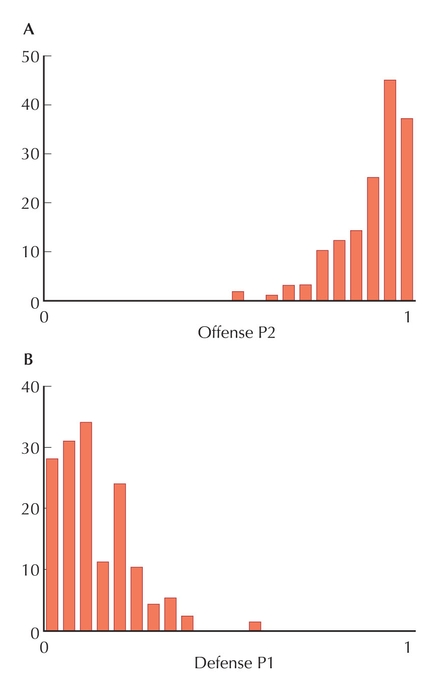

Figure WN20.9.

There is wide variation between genotypes of Drosophila melanogaster in sperm competition. Clark et al. (1995) studied 152 lines that had each been made homozygous for a particular second or third chromosome from a natural population. Female flies were mated first to a male from a laboratory stock carrying eye color markers and then to a male from one of the 152 chromosome lines. The proportion of offspring fathered by the second male gives a measure of the ability of that genotype to displace sperm from the earlier mating (“offense,” A). In the converse experiment, females were mated first to a wild-type male and then to a male from the standard laboratory stock. Now, the proportion of offspring fathered by the first male gives a measure of “defense” against sperm from later matings (B). The variation between the 152 homozygous genotypes is statistically highly significant. (Redrawn from Fig. 2 in Clark et al. 1995.)

|

|

|